A Woman’s Search for Meaning: on motherhood and writing the self

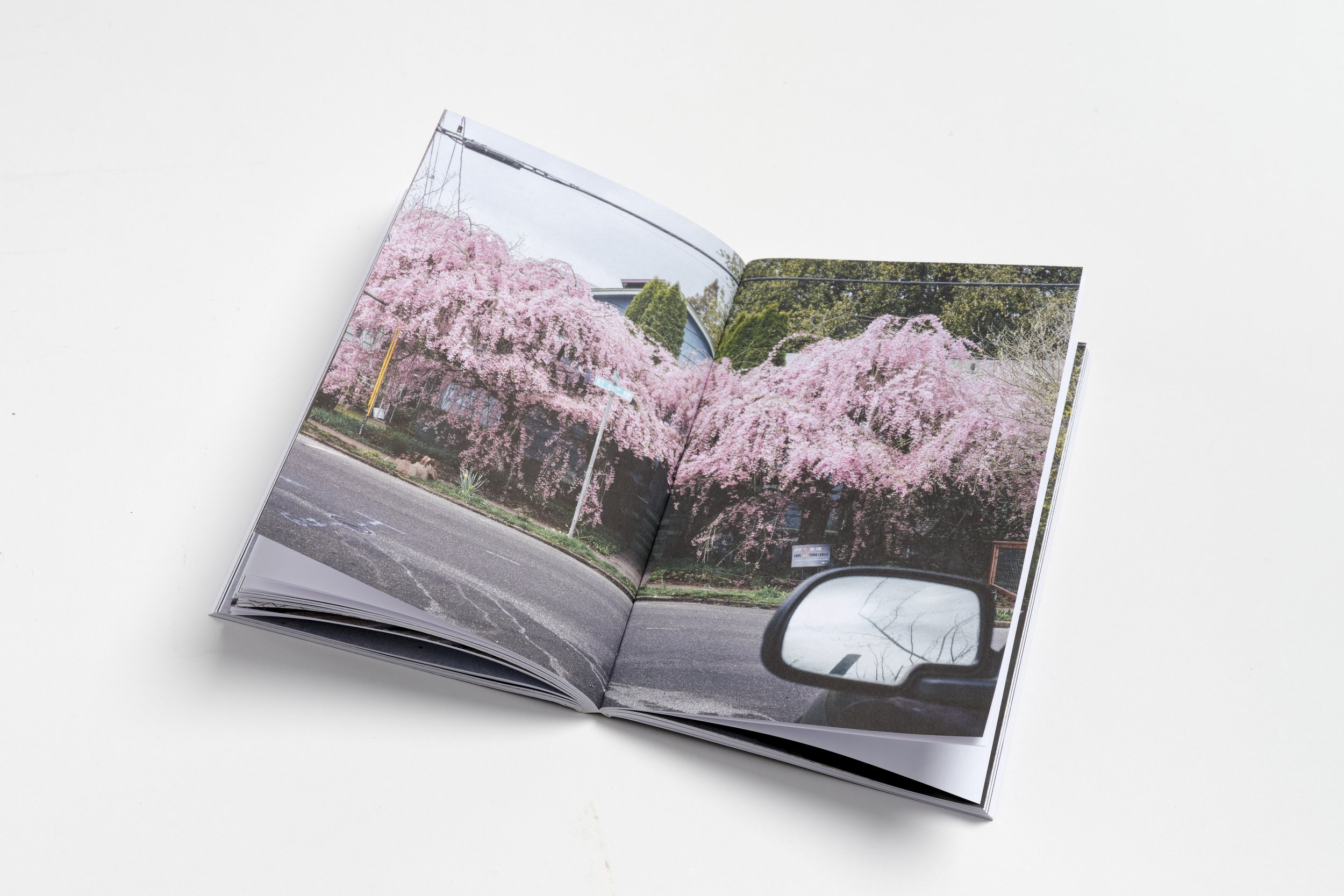

Essay by Frances Badalamenti & Photography by Aaron Wessling

When I became a mother, I had just lost my mother.

As I was learning to love my child, the stages of grief ripped through me, a wild convergence of hormones and emotion. It was already more than enough to have just had a child, and it was even more to lose a parent. I was grief-stricken, but I was also blissed out. You can read about the love you will have for your child, but you quickly learn that the feeling is beyond comprehension, like nothing you could ever imagine. I guess you can say the same thing about losing a parent.

It has taken me quite a while, but I can now see myself clearly during that time:

The light is filtered, subdued, moody. My child and I are wandering around our inner Northeast Portland neighborhood. He is holding a big rust-colored leaf in his hand. Because of all the bad sleep and exhaustion from new motherhood and grief, mixed with the strong coffee, my inner landscape is rough. As we walk, the houses and streets and parks fade into the background.

The boy comes into a clear focus. He is just a year old, strapped into a mint green stroller. I can’t tell if he is flashing a face full of gums and smiles or a face full of tears and screams. Because we still shared a body, my body, his body–he inevitably processed the same shitstorm of emotions as I did while I was pregnant. There were many instances when I didn’t know if my mother would live or die and when she did die, I fell to the ground holding my belly. We fell together, me and my child.

When we ask people about their relationship with certain family members, we ask if they are “close,” if they were close. We mostly know what close means and what not close means.

My mother and I were not close.

I didn’t confide in her about personal matters, nor did I solicit her for advice. But even though she could be chaotic, unstable, and unreliable, she remained a consistent part of my life until her death. When I lived a car ride away, I visited at least once or twice a month. After I moved away from the east coast, we spoke on the phone at least once a week, me in my tidy craftsman home in Portland and her in a dated rented condo in central Jersey.

Even when we lived on different coastlines, which we did for the last seven years of her life, I don’t recall missing my mother. I could also never imagine not talking to her regularly. She was woven into my being in myriad small ways. She would call me to set my clocks back or forward. She taught me how to properly fry breaded chicken cutlets. But when she would cross a line with me, from minutiae into actually intimacy, I would say, I gotta go, Ma. I didn’t trust her, so I didn’t share too much with her.

My mother loved me like nobody loved me and like nobody would ever love me again. And I love my child like I had never loved anyone before and would never love anyone again.

The loss of this is what broke me. However “close” we appeared. The very presence of that love steadied me. Made me feel at home in the world.

In her book Aftermath, Rachel Cusk writes, “Grief is like love but it is not love.” When I didn’t know what to do with the anger and the fear that came for me in this grief, I began to write. I knew that writing was better than throwing a highchair against a wall or raging at my spouse when the baby was sleeping. Like a young child, my emotions were unregulated and unchecked, but I had enough insight to know that for me to be a better mother than my own mother, if I wanted my child to trust me, that I had to do something with these emotions. I got help and I began to write.

Writing was obligatory.

I first wrote a memoir about losing my mother that I turned into a novel and then I wrote a twenty-something 1990’s coming-of-age novel that was closer to autobiographical fiction. These are my first two books and I believe that they had to be written to make way for the third. Like relationships, with books, it seems that the last one paves the way for the current one.

I tend to now write and teach what critics might consider autofiction, an often fragmented, nonlinear, free-form style of writing that has garnered both attention and criticism. Writers of notoriety associated with the tradition include Karl Ove Knausgard, Ben Lerner, Sheila Heti, and Rachel Cusk. Even though these writer’s books are beloved, autofiction has become a loaded term in recent years, one that some writers disavow, and one that many critics like to hate on.

After writing my first two books, I craved not just a veil, but a disguise. I felt shelled from a few experiences that I had after publishing them. The first book gave me something of a nervous breakdown, even though we don’t use that terminology anymore. Nonetheless, I was cracked into shards, and it took a lot of time and resources to put myself back together again. The second book pissed somebody off, someone I didn’t expect to piss off and that made me scared to write from my own life again.

So I found my way to autofiction, to writing that is outside of the linear, traditionally literary memoirs and novels.

You often see autofiction defined as fiction that is drawn from the author’s life. As much as that is true, that’s not the whole picture, because I don’t believe that autofiction can truly really be defined. And I say that because autofiction is not really a genre–it’s more of a style or a lens to write through.

You know that you are reading autofiction when the writer and the narrator become hard to differentiate. You are often led into the story in a very intimate way, but you are also kept at a distance, which ups the intrigue. You can’t tell if you are reading fact or fiction and if you are curious like me, you will try to piece together clues with fragments from the writer’s actual life.

For someone like Lucia Berlin, a writer that is known for her autofictional short stories about drinking, failed marriages, and single motherhood, it is an easy sleuth because of Welcome Home, her posthumously published memoir with accompanying photos. You can read her stories and then find hints and echoes in the memoir.

Chris Kraus has spoken candidly about her novel, I Love Dick being about her obsession with cultural critic Dick Hebdidge while she was married to theorist, Sylvère Lotringer. Sheila Heti writes about her friendship with a character called Margeaux in her “novel from life” How Should a Person Be? which she openly discloses is based on her actual best friend and confidante, the Toronto painter, Margeaux Williamson. Ben Lerner openly talks about his novel The Topeka School being not just inspired but extracted from growing up around his parents and their jobs as psychologists at The Menninger Foundation in Topeka, Kansas. And Karl Ove Knausgard famously pissed off his uncle and his ex-wife in the writing of his six-part tome, My Struggle.

But in the end, it’s not necessarily about the differences between what happened in real life versus what has been fabricated–it’s much more about the emotional landscape of the character that the writer inhabits. It’s the visceral, existential nature of the work that we connect with, not unlike reading poetry or listening to music. The closeness to lived experience can reify the pulse of the writing, offering a way in, a path to deeply connecting with the character.

And like all art, that, of course, can be very subjective. Not everyone has a taste for the nuances of autofiction.

In my classes, student writers frequently endeavor to understand how autofiction differs from memoir, because it can be hard to tell the difference. I draw a slapdash Venn diagram on a notebook and hold it up to them. One half is memoir, and the other half is autofiction, the shared slice in the middle is: “taken from personal experience”.

I often tell them that the more you read this style of work, the more you will understand, because it can be quite hard to articulate. It’s more like a feeling, a feeling that you believe you really know the narrator, like you are sitting with them sipping coffee in their kitchen, hearing from them firsthand. Whereas in memoir, you know it’s truth, so you hover on the outskirts a bit, looking inwards, sipping coffee in a café and observing the narrator at another table.

I don’t believe that autofiction is voyeuristic like memoir is–it’s more that the reader of autofiction becomes part of the story. And maybe this is what some people are turned off by. They want to hover because it’s too intimate, otherwise, that line is crossed. Autofiction taps into the self in a way that often triggers universality. Memoir can certainly do the same, but I would argue that memoir more so triggers relatedness. We relate to someone’s plight in a memoir. In autofiction, we enter it; wringing our hands along with our protagonist.

When I sit down to write, I am using an experience from my past, something that nags at me, a piece of unfinished business. The scene plays out in my head, not unlike watching myself in a movie, but instead of writing that scene verbatim, I siphon out the emotion and try to render that on the page. I might include some details, but the net result is often a composite of various experiences and people. My former self, the self that had been through the lived experience has now merged with my current self, the one that is writing the scene.

Some consider autofiction navel-gazing, a lazy, lesser art form because it can’t be that hard to make story out of your own life, right? I’ve heard the same thing about memoir. Saying writing is lazy is lazy itself. And I consider creating a narrative from self a radical act–a high art.

In recent years, there has been a trove of women writing and publishing books about their inner struggles and identities as mothers. It seems to be in response to how disconnected we feel with the feminist landscape. How we see gender and what we feel about patriarchy continues to shift. As mothers, there is a history of us being looked at as “bottom feeders” of society because even though some of us have careers in addition to mothering, it seems that really all we are required to do is sit on the couch and make sure our children don’t fall out of an open window. And it’s certainly no coincidence that autofiction, which is associated largely with women writers is derided or looked down upon.

I am thinking of writers like Rachel Cusk, Kate Zambreno, Kate Briggs, Olga Ravn, Sarah Manguso, Jenny Offill, and Rivka Galchen. And I see their predecessors as Annie Ernaux, Lucia Berlin, Tove Ditlevsen, Yuko Tshushima, Natalia Ginzberg, and to a certain extent, Grace Paley.

These narratives about motherhood are often comingled with the men and children in our lives and the divisions of labor that intersect with and haunt our relationships. We write about the sacrifices and the gender roles and the societal expectations of both women and mothers in order to make meaning out of the struggle. I recognize that not everyone in this predicament experiences struggle, but I want to emphasize that the struggle that may result from identifying as a woman and a mother is a specific brand of struggle.

And this is the struggle that these aforementioned writers set out to unravel for us on the page.

I began working on my third novel, Many Seasons, during the heart of pandemic. Society was unraveling, and our collective sense of self was under extreme scrutiny. We didn’t know what to believe, who to trust, or what was ahead of us. It was a time to take stock of our lives and our relationships and an opportunity to look closely at our inner selves.

I remember cooking big meals in the middle of the day. I recall my head hitting the pillow as if I had just run a marathon, even though the most physical thing I did was take the dog for a walk through my deserted neighborhood. And just as I did when I was at the emotional crossroads of grief and joy after I became a mother, I turned to the writing for solace.

I had been gathering scenes and vignettes for about a decade prior, a means of archiving the desperate, isolating, and often mundane life of my role as the primary caregiver of my son. In my mothering, I had also become a non-income producing householder who depended on my male spouse for financial support.

There was something interesting about the boredom and the minutiae of everyday pandemic life, how everything that I had been writing about became distilled and slowed, the aperture narrowed. When everything screeched to a halt, I had a deep well of material to access. What I came to realize is that these vignettes or snapshots had been a long-running investigation into my identity as a woman and a mother.

Sarah Manguso writes, “After I became a mother, I learned that I am a woman, and after that, I learned what people think of women. It happened very fast.”

When I transitioned into the more “feminine” role of non-income producing mother, I lost a lot of my autonomy. My self was dismantled. I couldn’t fully share my internal struggles with others around me, because on the surface, I was in such a privileged position. You are just so lucky to be able to stay home with your child. What those around me didn’t realize back then is that I had also lost my voice and was grappling with who I was as a person in the world. And that’s when I began to write through the struggle, because that was the only place I felt that I was allowed a voice. I would find a way to write about both the struggles and the interiority, eventually through a more autofictional lens. That lens felt safer, more secure. In other words, I could write like a man, without that fear.

I am about to publish my third book, the most distanced, yet the most personal–I continue to investigate how I see myself in the world, through writing, through personal work. What I have found is that I no longer see myself solely as a mother and a woman–I see myself as a writer.

Because when we allow ourselves to identify as an artist, we lay claim the self, let it be seen, and even accessed and related to by putting it on the page and out into the world.